December 2011

Related

Language

The Inside of the Outside

Living in an Urban Landscape

Walking through Tokyo,

I often think of—

and probably look like—

Foucault’s Renaissance madman:

Confined to a ship,

adrift on the vast ocean,

traveling in the interior of the exterior.

It’s an image that stays with me.

Not just as metaphor—

but as a way of experiencing the city.

Tokyo is that ocean.

A sea of infrastructure.

Of overlapping systems.

In this ocean, we don’t arrive.

We drift.

We navigate.

We move.

Eventually, we’re told,

the ship reaches land.

The journey ends.

But what if it doesn’t?

What if the land itself

is just a continuation of that sea?

What if buildings are not closed objects,

but part of an endless ocean?

A city of buildings

that don’t shut themselves away—

but remain in motion.

Where we do not settle,

but keep moving.

Where buildings are not simply in the environment—

but are creating it.

Actively.

Fluidly.

Endlessly.

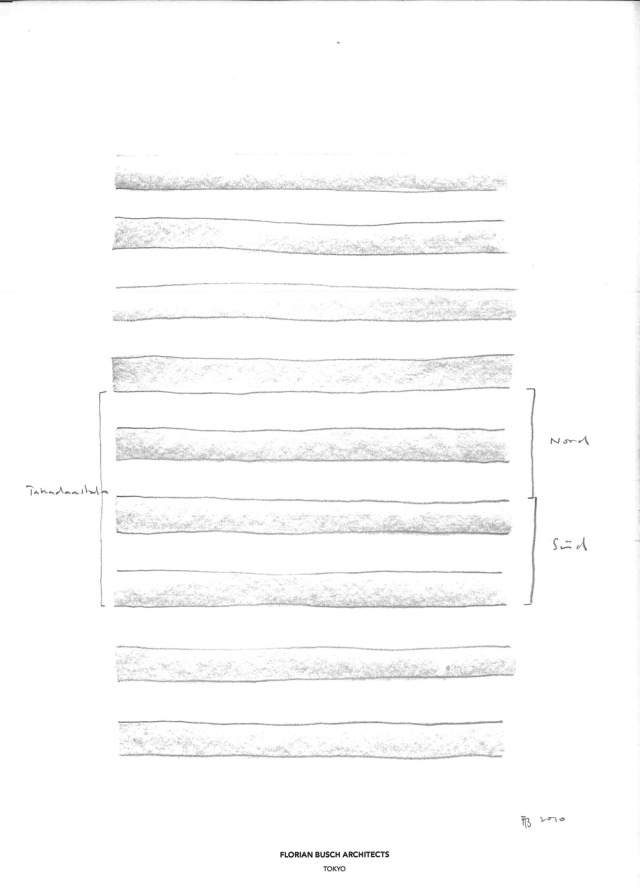

The Folded House in Takadanobaba is

a house—

but not really a house

as we usually think of it.

Sitting between heavy masses,

in a narrow 4.7-meter-wide strip,

the house doesn’t impose itself.

It folds.

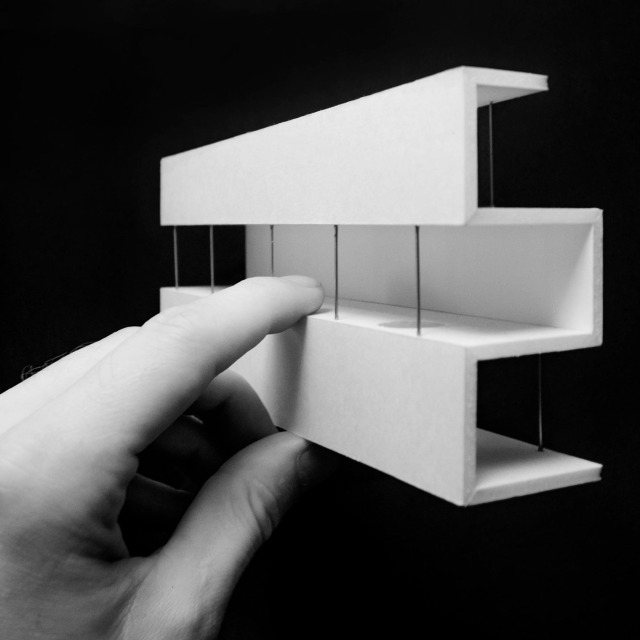

A thin plane,

growing upward

through a gap the city forgot.

The built is but a snapshot of that process.

Its structure is fine—

almost delicate.

It exists not against its neighbours,

but with them.

Solid versus open.

Mass versus lightness.

The spaces we create

don’t enclose.

They extend.

They continue the city

on vertical trajectories.

The house becomes

an urban landscape

unfolded upwards.

Tokyo is full of these gaps.

Slivers left behind

by endless subdividing.

Once they get too small, they’re often ignored,

deemed too difficult to deal with.

But in these interstices,

we see something else:

A different kind of potential.

The Folded House takes the leftover

and makes it liveable.

Not through conquest—

but through continuity.

This is how a building becomes

more than a building.

It becomes

a prototype

for a different way of living

in dense urban environments.

That idea extends into the structure itself.

The fold isn’t just a gesture.

It’s a system, open to grow.

The concrete fold:

a surface carrying load;

in between a few 80mm slim steel supports,

freed from horizontal loads.

The structure enables the space.

It doesn’t dominate it.

It lets the house be

what it needs to be:

open, vertical, flexible.

And then,

there is time.

Season.

Change.

To live with the seasons

is a quiet luxury.

In this house,

you live with the sky.

With air.

With shadow.

Soft fabrics

filter the light.

There are no partitioned rooms—

just gradients.

The house feels

less like a container

and more like a field—

a landscape that flows

with your life.

It’s a house that isn’t a house.

Not in the traditional sense.

It’s a shift in how we define space.

How we live with the city.

And how the city might live with us.

It doesn’t solve the urban condition.

It questions it.

Living in an urban landscape

means existing in a field

of continuous negotiation.

Between structure and void.

Public and private.

Enclosure and openness.

It’s not about containment.

It’s about resonance.

Movement.

Possibility.

The Folded House

doesn’t fill the site.

It reveals it.

It doesn’t isolate from Tokyo—

it becomes Tokyo.

Architecture

not as monument,

but as movement.

Not as object,

but as environment.

Asking how we might live

in the folds of the city,

we might find an answer in the inside of the outside.

—

FB, December 2011

Transcript of the speech for the opening of the “Folded House” in Takadanobaba