Kita Unga Hotels

北海道小樽市, 2019—

March 2020. Country after country is closing its doors. Pandemic uncertainty. Only a few weeks before, FBA had been commissioned to do a feasibility study for a hotel in a surprisingly neglected area of Otaru, the port city in Western Hokkaido which, a century ago, was one of the places to be in East Asia.

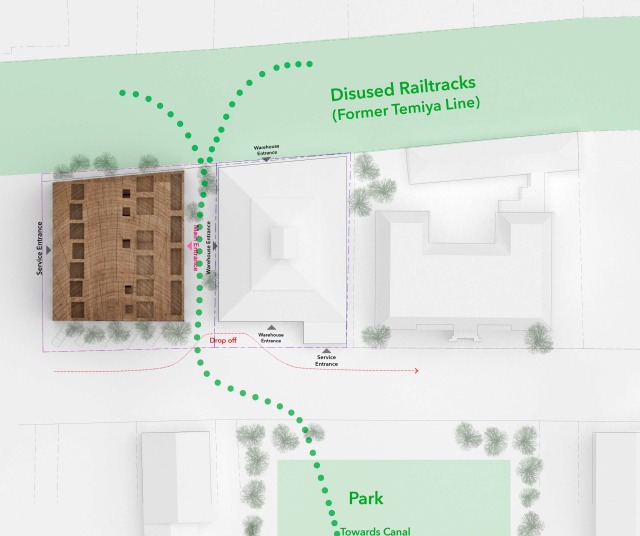

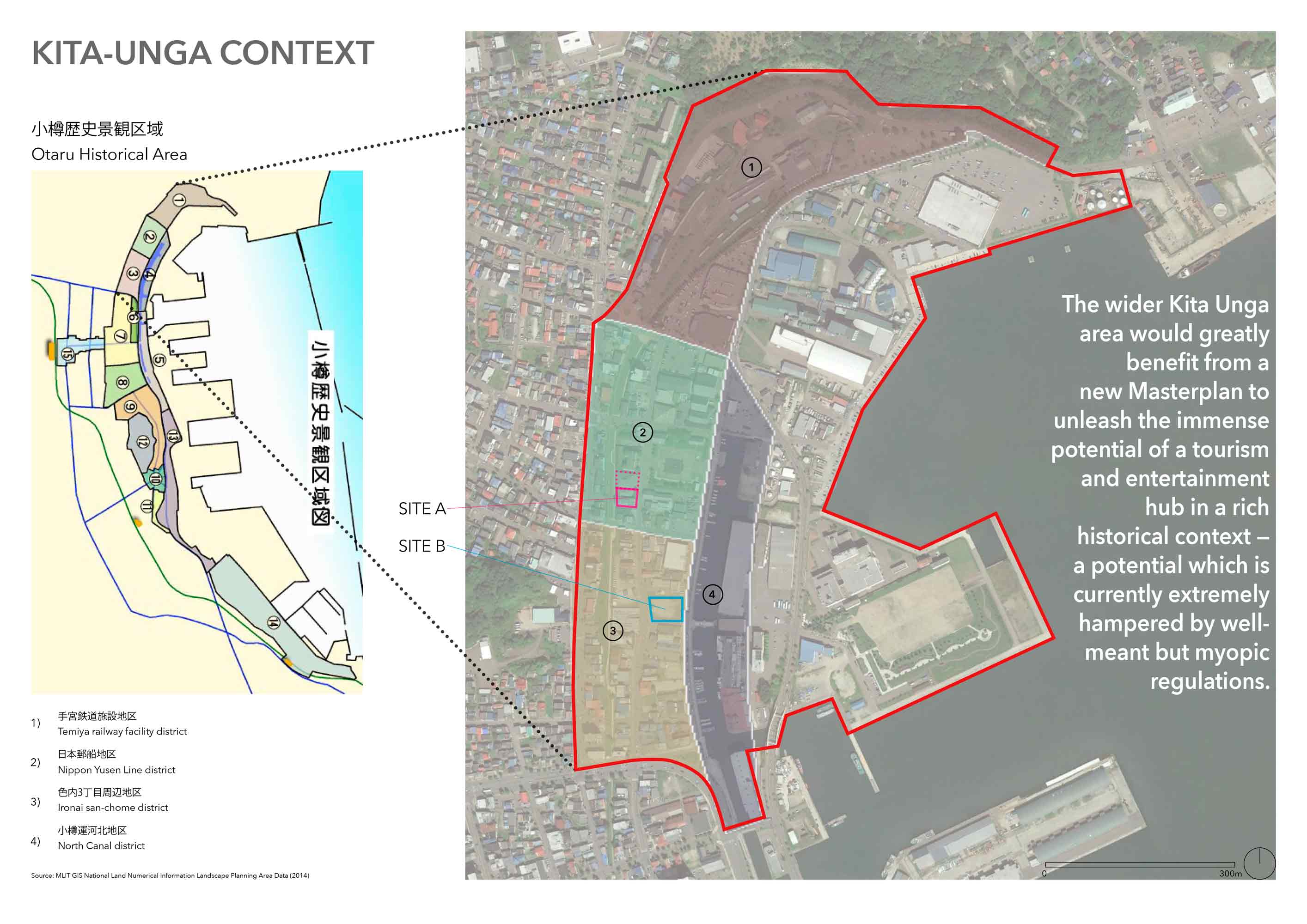

Kita Unga (“North Canal”) is testament to a time of Otaru’s heydays. Warehouse next to warehouse, built around 1900, some still in use, others emptied out, waiting to be rediscovered.

The client has made such a discovery.

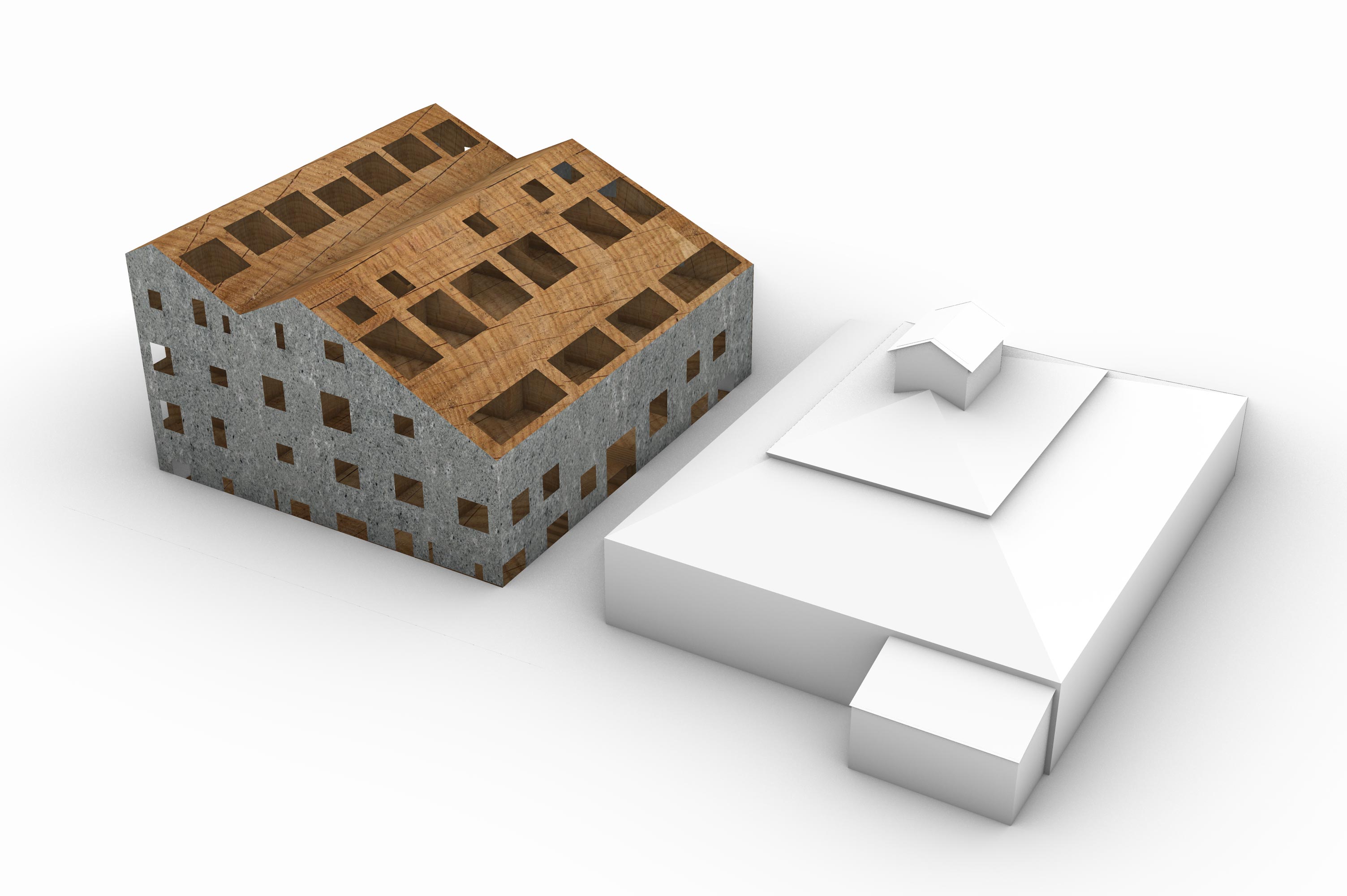

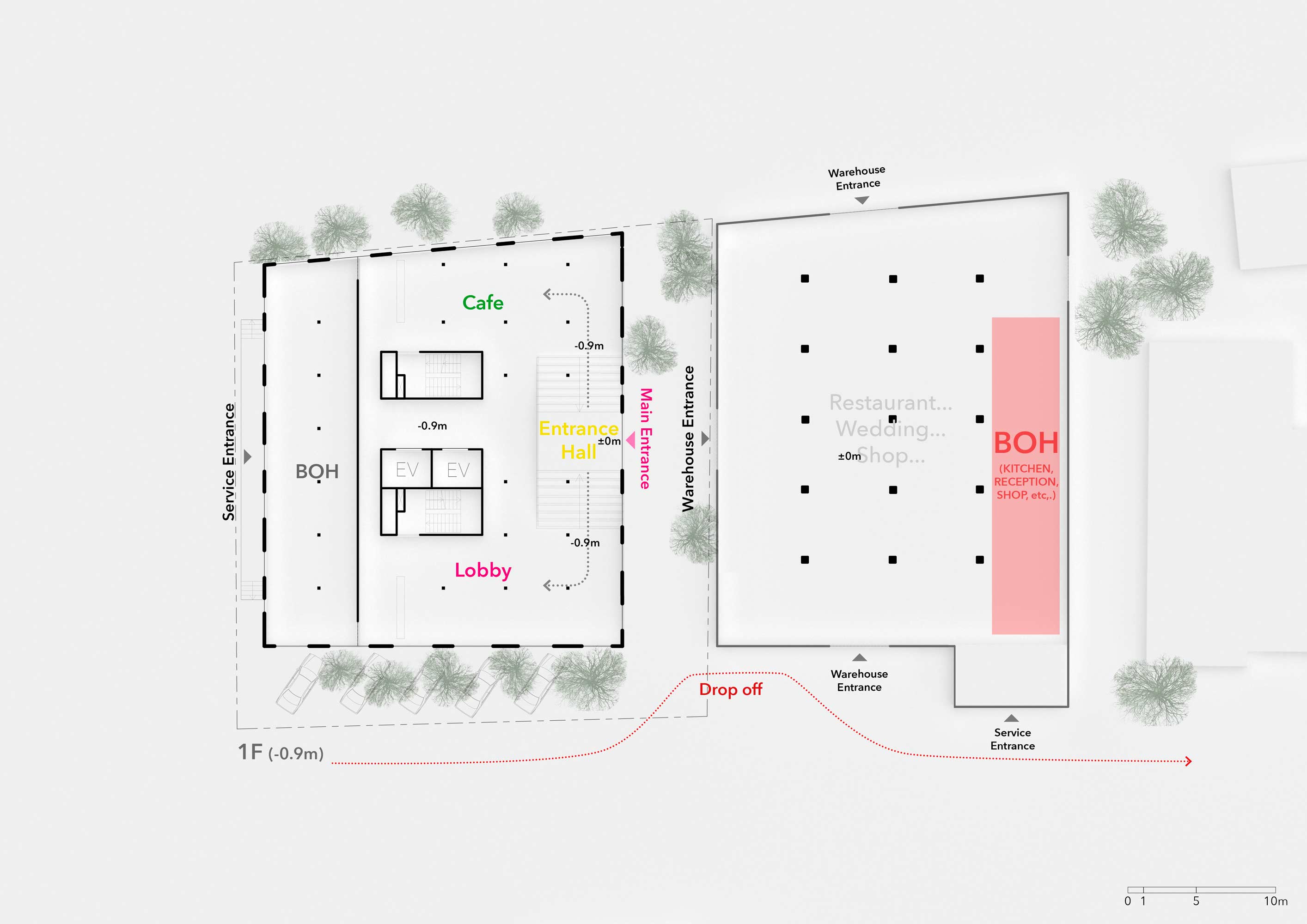

Next to Nippon Yusen’s (NYK) Otaru Branch, listed as one of Japan’s Important Cultural Properties, is its smaller storage building: A 120-year-old warehouse, built like many others in a mix of local stone and timber-frame. FBA is tasked to investigate the potential of this warehouse and an adjacent plot of land for a boutique hotel + venue ensemble.

Site A

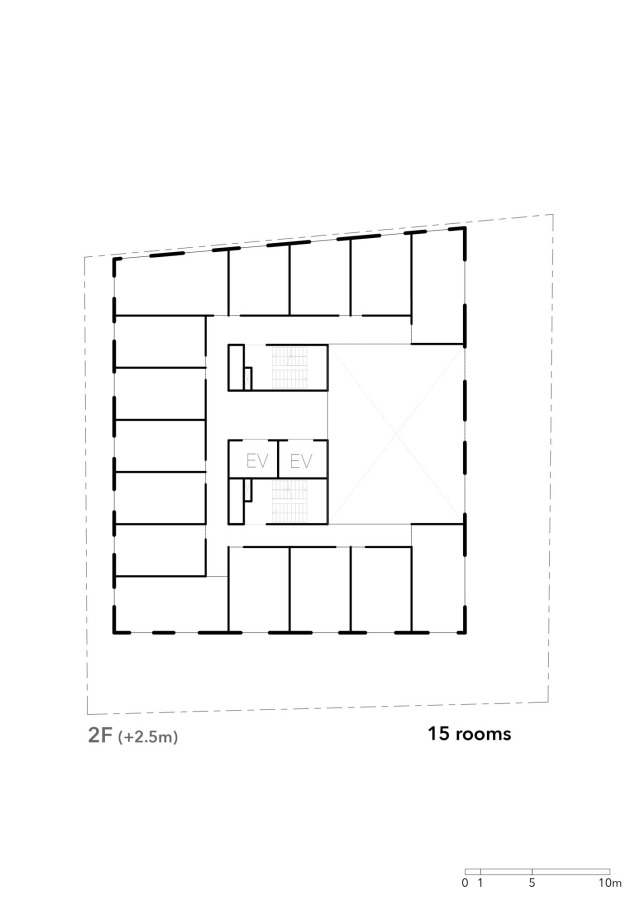

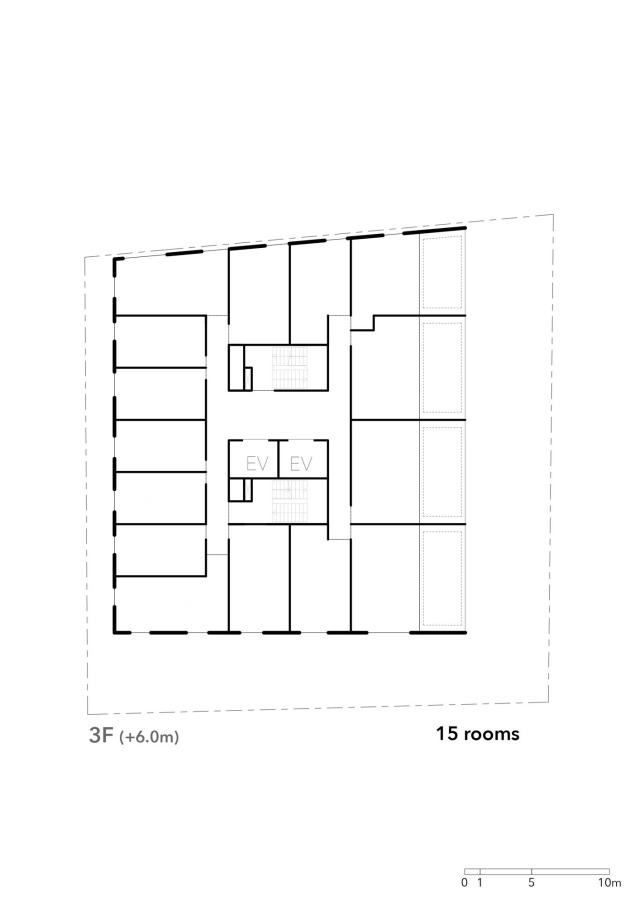

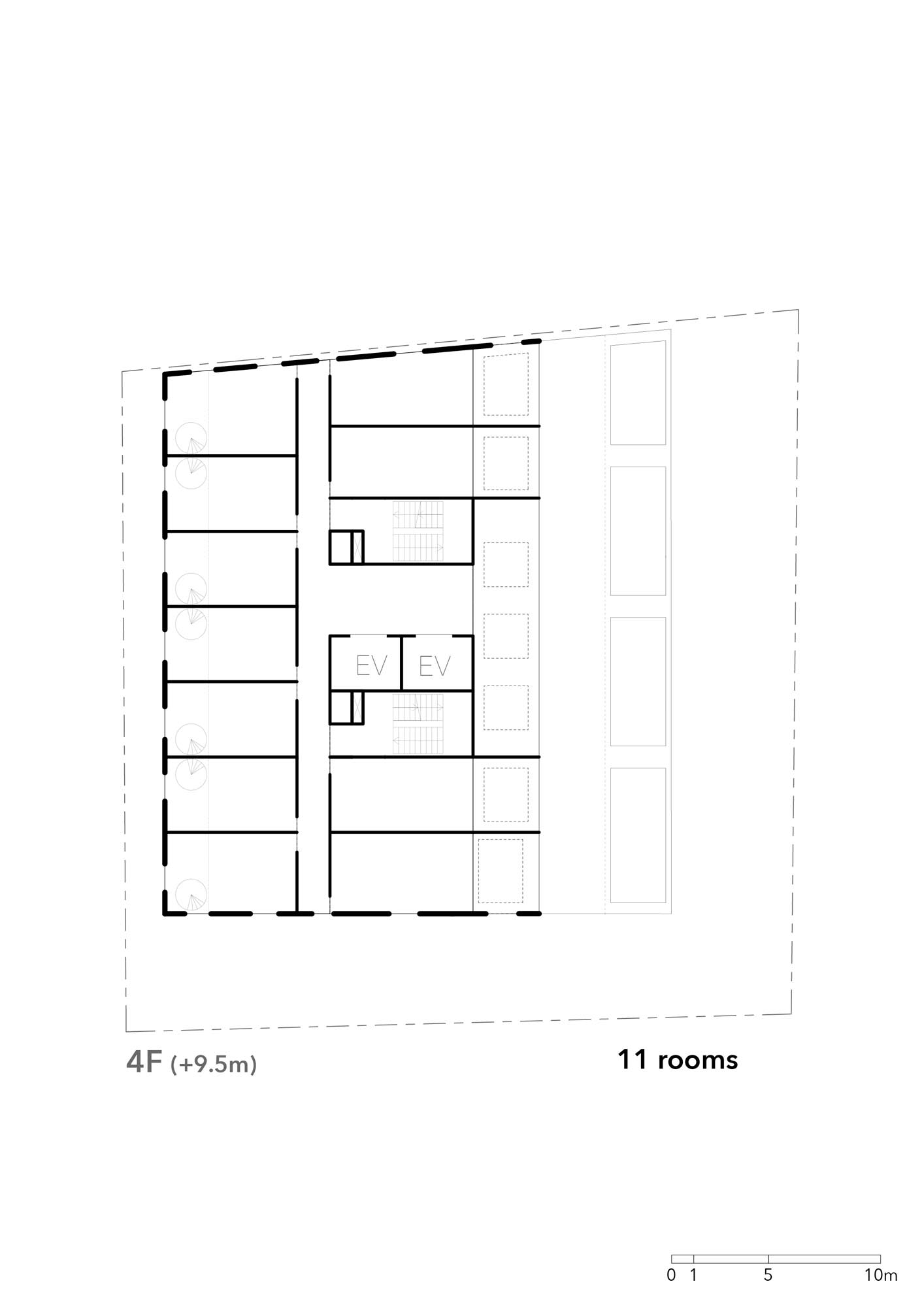

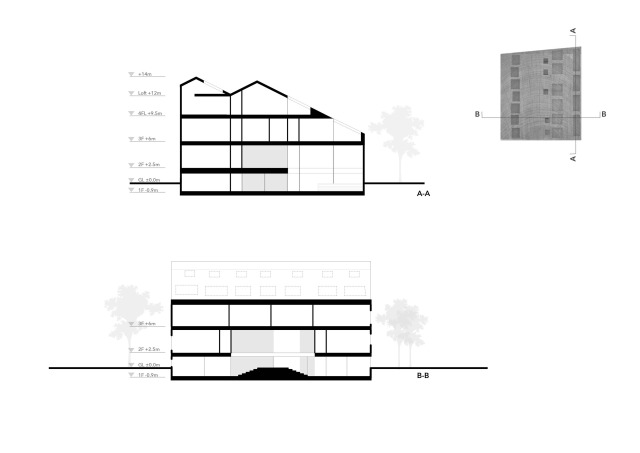

Site A embraces the old warehouse and complements the new hotel. Regulatory constraints when dealing with the listed warehouse will make any intervention a delicate effort. In order to maximise both the number and quality of rooms, the entrance to the new building is sunken, freeing up three levels on top — for a total of 41 rooms, 15 with private onsen terraces. The sunken level houses lobby and a small restaurant. As an ancillary to the warehouse, this can serve as breakout lounge.

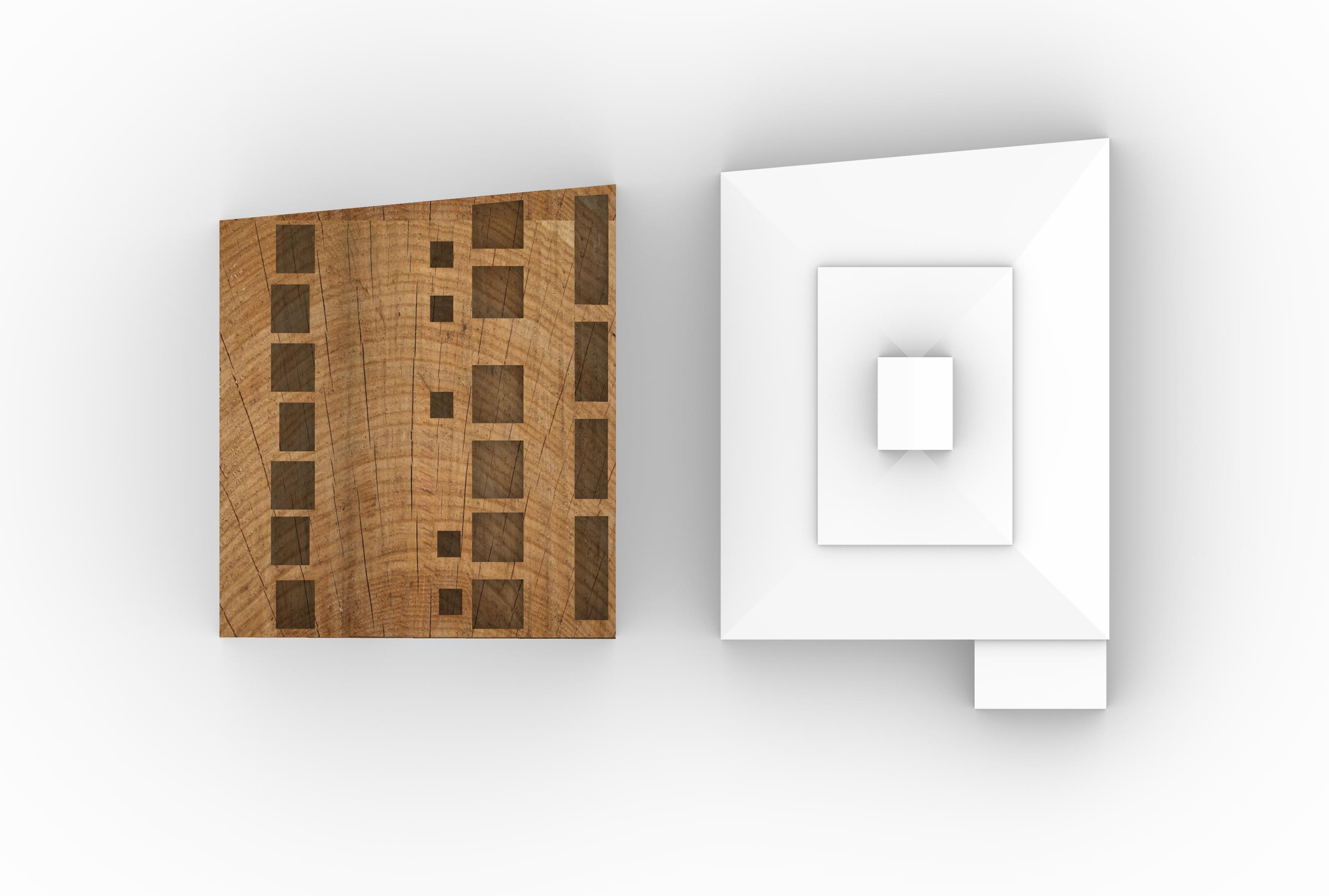

The old warehouses around us have led the town to impose restrictions: Issued around 2010, the regulations greatly define what is possible in the area. Three key regulations restrict the overall height and shape of the building: shadow lines, mandatory roof pitch, and maximum height.

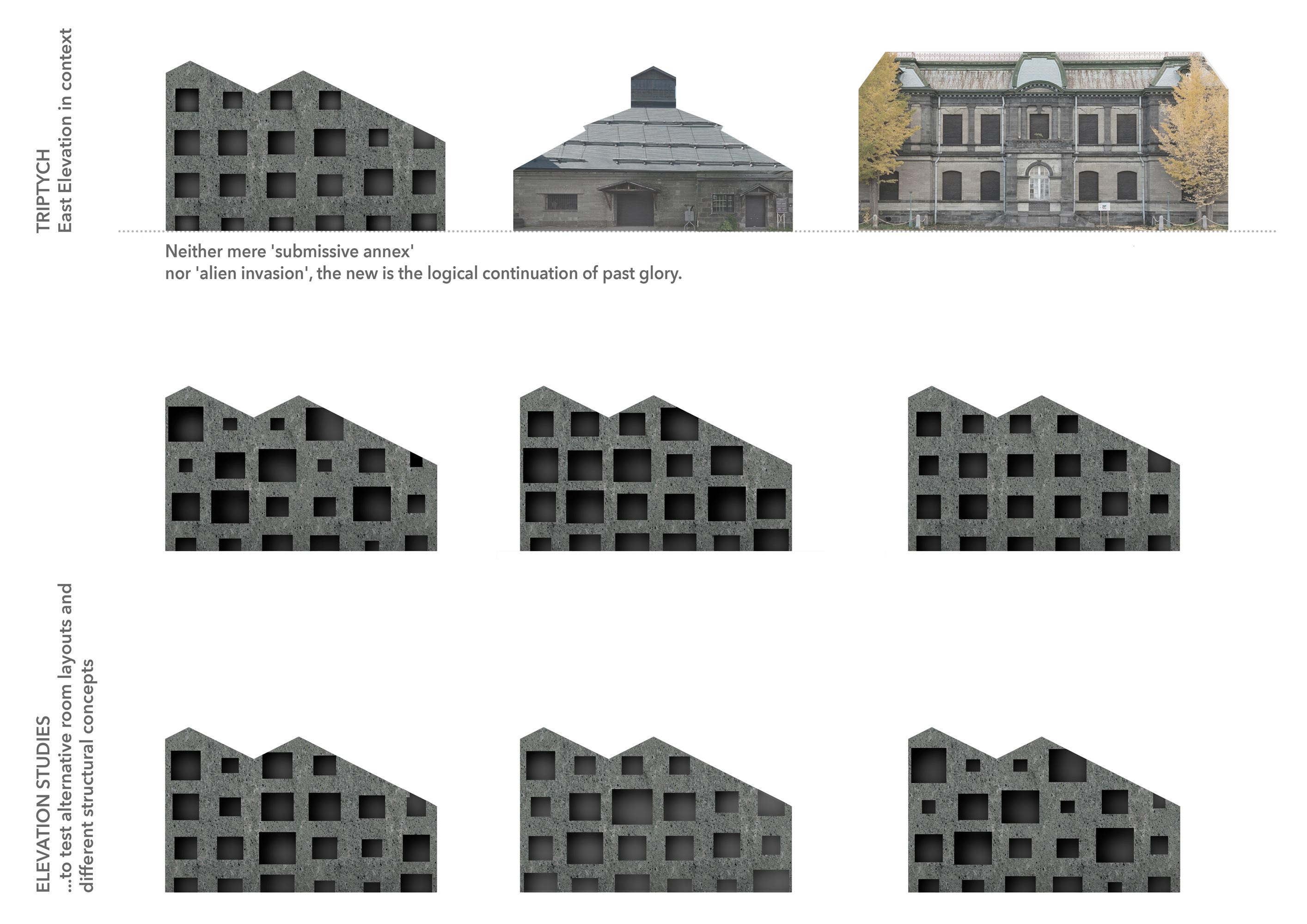

We propose placing a massive stone only to cut it in ways negotiating between these three restrictions and the hungry program of the hotel volume.

The cut —zig-zagging in order to find a volume for a maximum number of rooms— results in an unexpected double ridge.

The resultant mass is part of Kita Unga’s ‘warehouse vernacular’ and yet distinctly different. This simple strategy works surprisingly well in the context: The new is neither mere submissive ‘annex’ nor overwhelming the existing warehouse.

Of Visceral and Financial Sense

Just when our proposal manages to convince the client of the potential, another site only a few walking minutes away comes up.

This new piece of land is twice as big and, in comparison to the many strings attached to Site A, much more straightforward.

All of a sudden, we are dealing with two hotel projects, competing with, or complementing(?), each other: One makes more visceral, the other more financial sense.

Site B

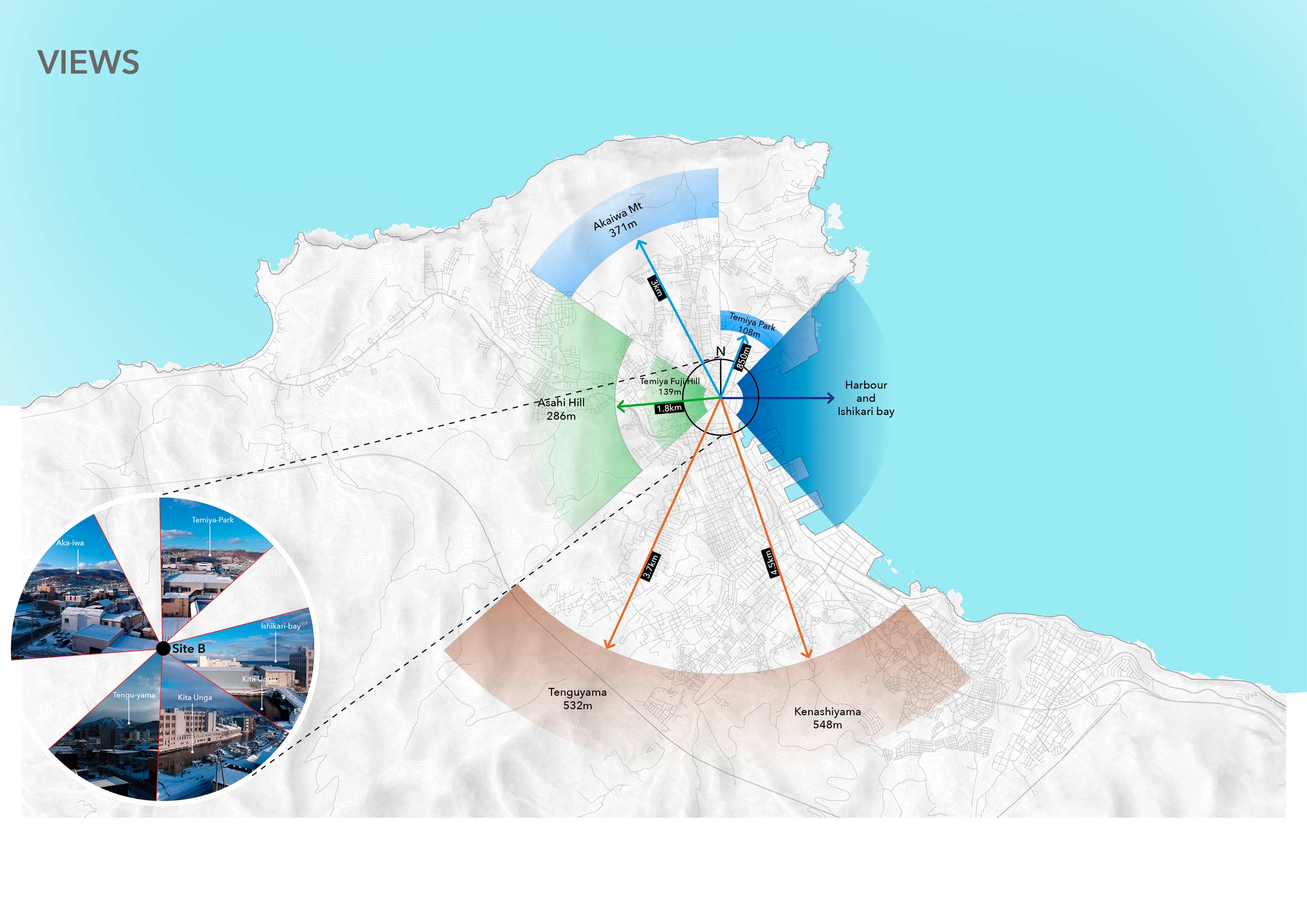

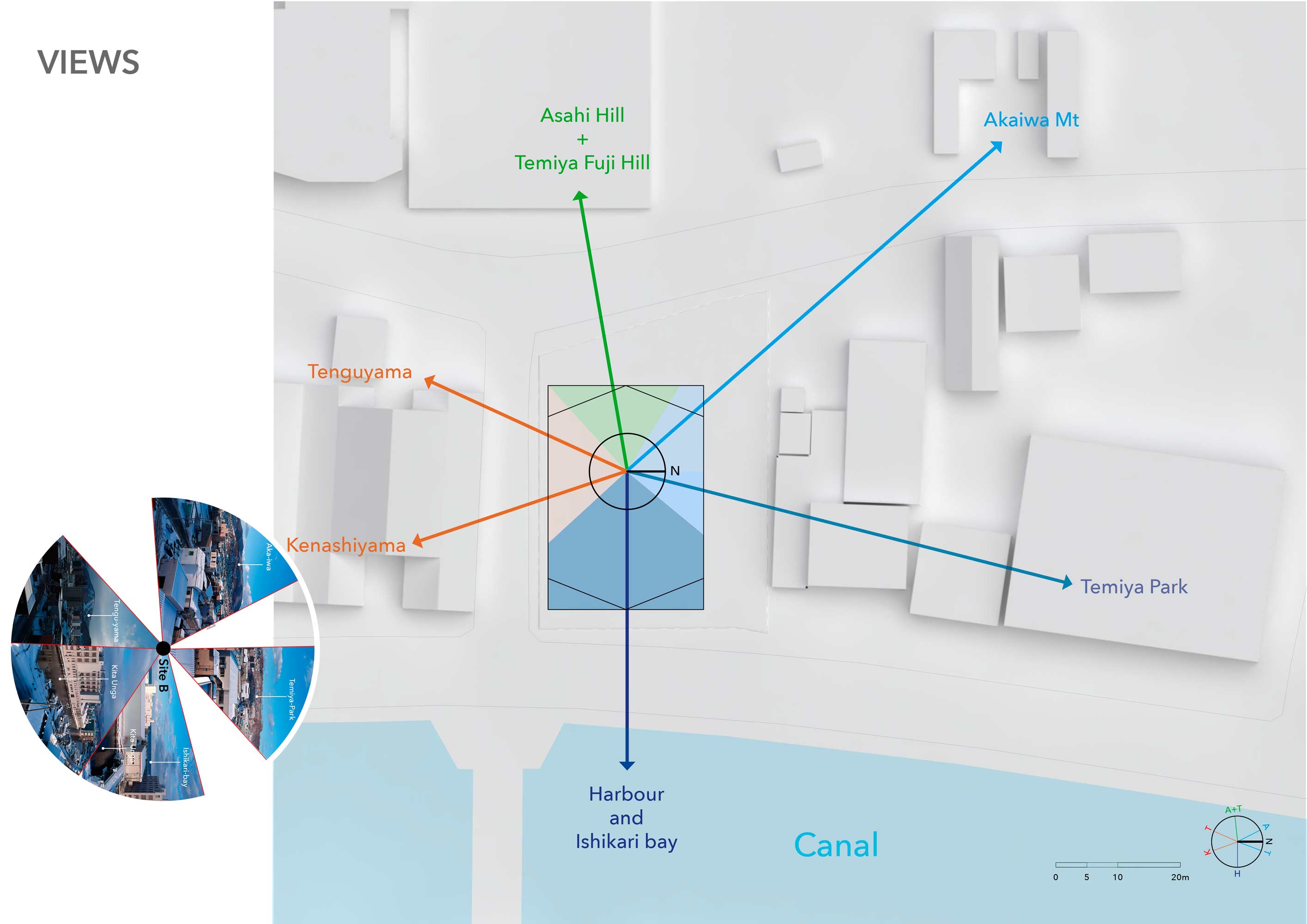

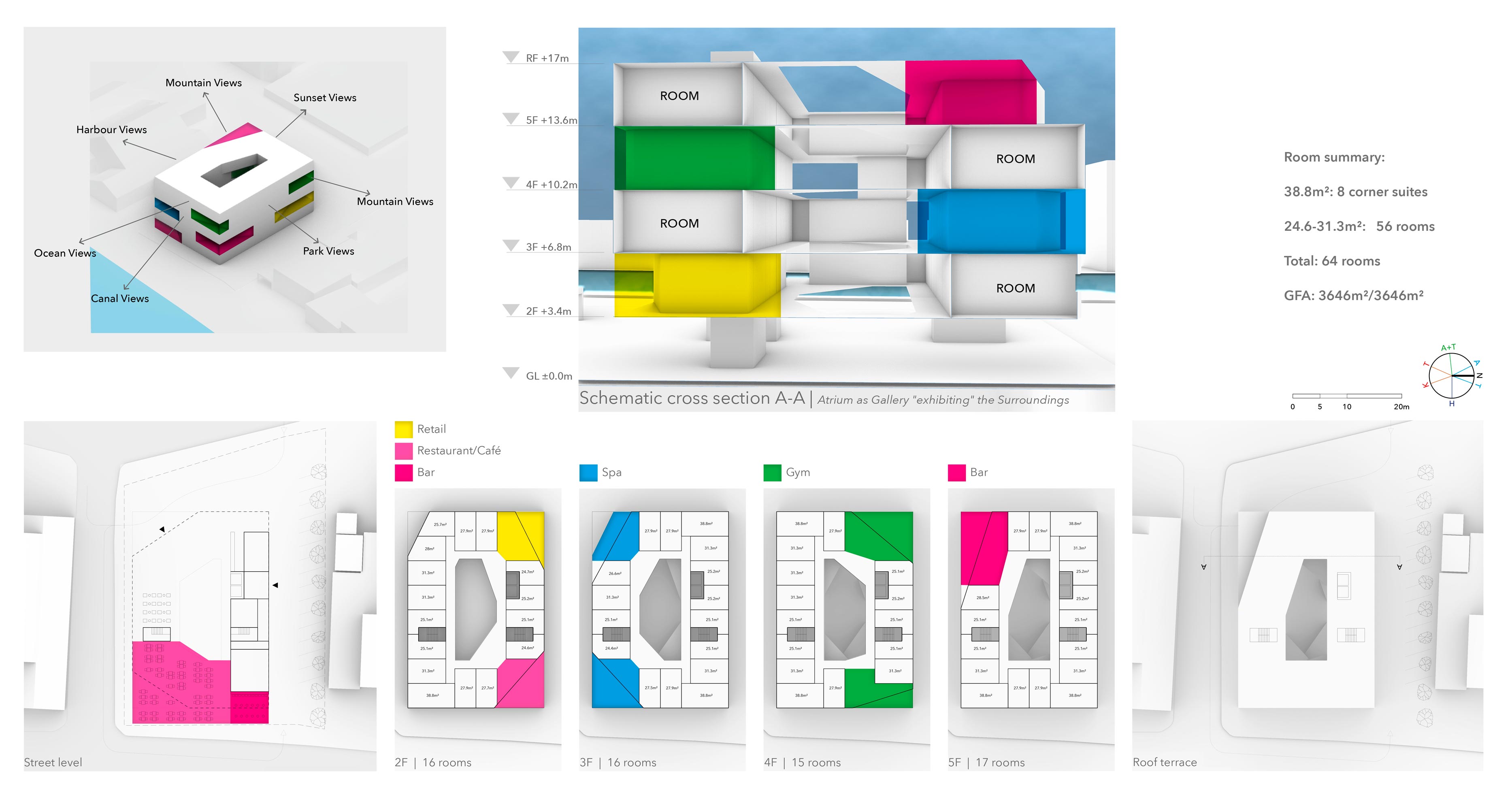

On Site B, the zoning laws are less strict. In addition to the immediacy of the Canal, the site has 6 distinct far views. Since the ratio max. GFA to max. footprint would be exhausted at close to three storeys, there is a high degree of freedom to deviate from the conventional ‘extrusion’ of the max. footprint since the height limits can result in up to five storeys.

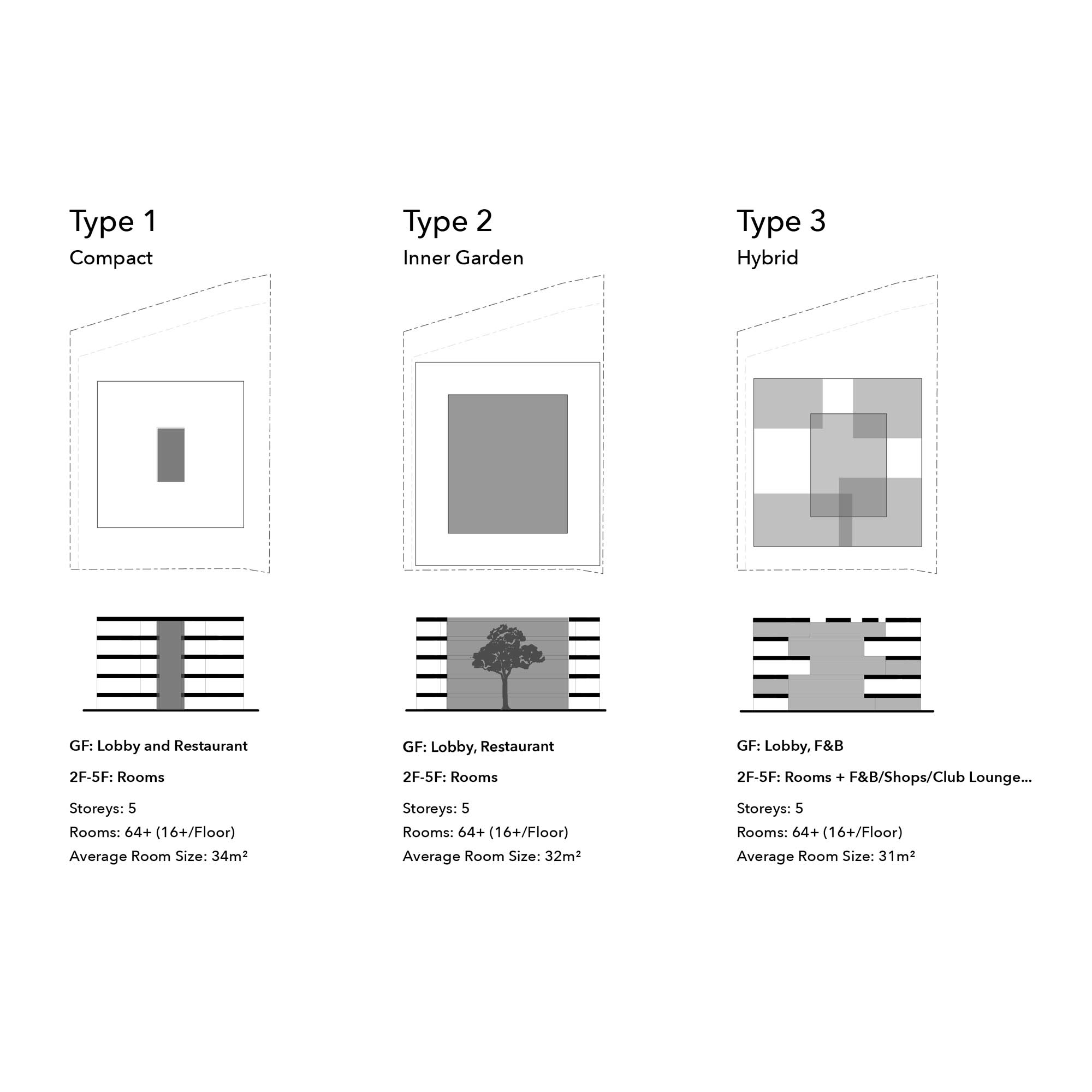

The conventional ‘extrusion’ (Type 1), is compact but fails to exploit what this site has to offer.

Type 2 maximises the circumference to open up an inner garden. A large part of this garden could be covered before reaching the max. footprint.

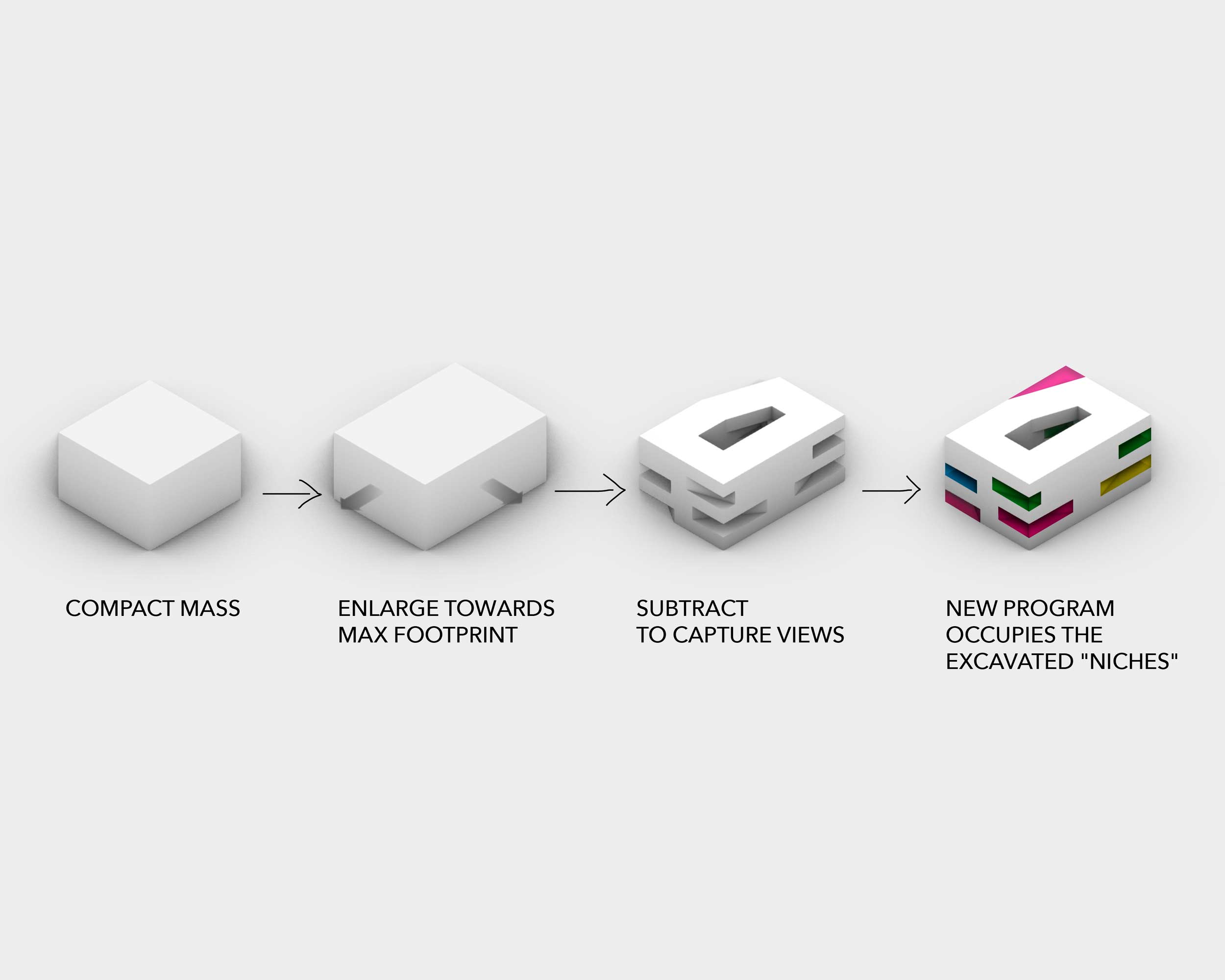

Type 3: A hybrid of Type 1 (‘compact’) and Type 2 (‘inner garden’) finds solutions between minimum and maximum footprints. Instead of a garden, excavating an increased mass generates niches for new program: The hotel is no longer the conventional layers of rooms on top of a lobby but the continuation of the city in three dimensions with rooms along the route.

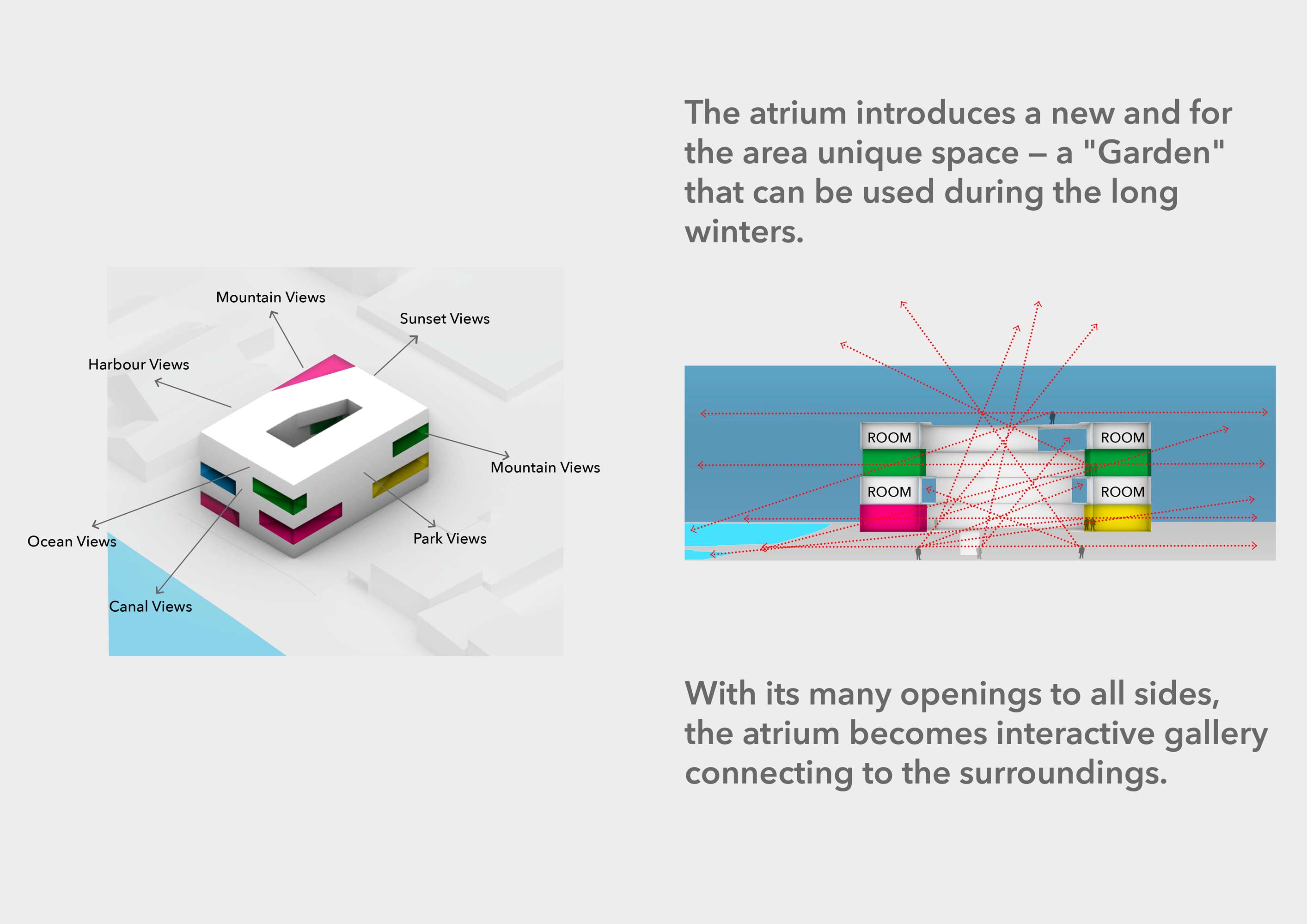

Exploiting the extra footprint opens up a distinct interior space. Spatial and visual relationships turn the (for a hotel) relatively small space into a generous experience. The canal, the mountains, the sky, all become backdrops of a dynamically changing environment. Instead of the monotonous repetition of stacked room floors, each level gets enriched by additional program (F&B, entertainment, shops, …) to attract a wider audience to the (still) remote Kita Unga area.

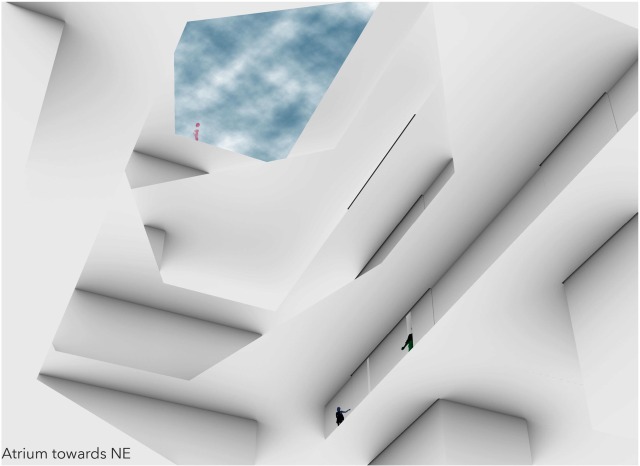

In the middle, a large atrium becomes an interesting new semi-public space — and since it is covered, also during the infamously cold Otaru winters. Around the atrium, strategic placement and orientation of the rooms can achieve a high percentage of ‘rooms with a view’.

Shutting down

Eventually, both projects were abandoned before we had even wrapped up our study. With the world shutting down, the pandemic left no room for hospitality.

Post-Pandemic Post-Scriptum: Untapped potential

As the world recovered from the pandemic, Japan was slow at reopening its borders. When it did, years of closure paired with a weak yen catapulted inbound tourism into unknown territory. For Otaru, Kita Unga’s rich heritage would seem like a fortune maker.

FBA’s analysis of the Kita Unga area uncovered even more than the obvious: There is a huge dormant potential in this area. Besides the old building mass with its many gems (the most prominent of which is Warehouse 3), there is even more to be discovered: An urban fabric that could be activated with very little effort, connecting old and new, ushering in a new golden era for Otaru.

北海道小樽市, 2019—

Type

Status

Team

フロリアン ブッシュ, 宮崎佐知子, ヨアキム ナイス, C. バウムガーテン, 大澤祐太朗, 島玲旺, 陳協志

Size

延床面積: 2,860 m² (Hotel on Site A (1944 m² in new, 916 m² in existing warehouse))

延床面積: 3,646 m² (Hotel on Site B)

Structure